![]()

![]()

Web Author: Juan Jimenez

© 1999 by Juan Jiménez - All rights reserved.

A mechanic pushed the plane out into the sunshine, not too difficult, because pilot, plane, and fuel weighed under 600 pounds. Les fired up the German-built two-cylinder Hirth snowmobile engine and revved it to 6500 rpm. It sounded like a baby banshee.

"Okay," said Jim Bede, beside me. "I can't prove all my claims in an hour. But at least you'll see my plane can actually fly."

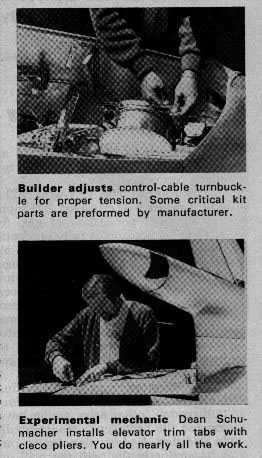

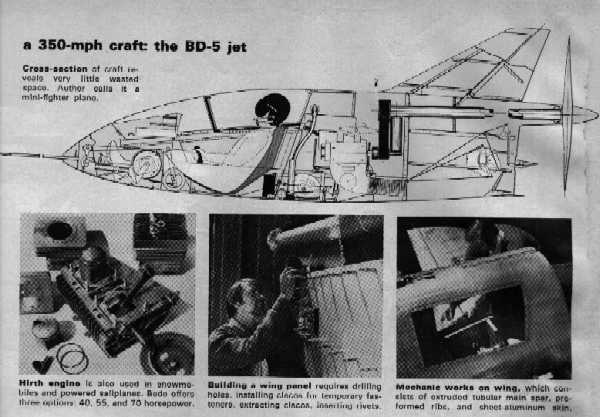

The claims? The long-wing BD-5 55-hp micro will cruise at 200 mph, get 38 miles per gallon of gas, fly 1215 miles nonstop, is fully acrobatic (with short wings), yet performs almost like a sailplane with long wings. All through the BD-5's growing pains, aviation experts have been needling Jim about his optimism, telling him it couldn't be done, and even accusing him of deliberately painting too rosy a picture to help promote what they felt was going to be a flat-out bust.

Les Berven taxied off down the big concrete runway at Jim's Newton, Kans., headquarters (an old B29 field). The sky was blue and smogless. The flat lands stretched off in all directions like an enormous pool table. Far off, looking like a red-and-white bug, the tiny plane turned into the wind and we heard its engine begin to scream.

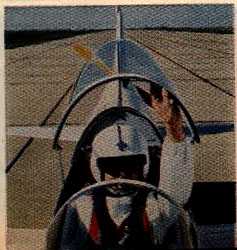

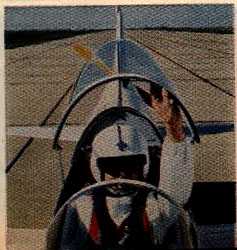

"Hold onto your hat now," muttered Bede. The bug moved forward slowly. It gathered speed, and lifted off. Then its tricycle gear snapped in like a switchblade. The plane went skimming past in a climb, resembling an F-104 jet fighter. "It's not going as fast as it seems," said Bede. "It's so small, you get the illusion of higher speed." It wasn't exactly standing still.

Half an hour passed. Then word came over the radio from Berven that his fuel pressure had dropped to zero and his engine had stopped running. Bede, hearing this, merely smiled. "No sweat, he's got the long wings. He could glide to Wichita if he had to." (Wichita was 15 miles!)

Berven circled the field like a sailplane, without power. He S-turned to kill excess altitude. He landed like a feather and rolled along to the feeder runway serving Bede's test hangar. The test-pilot turned in, coasted to a stop beside us, and raised the canopy. "Nuts, I intended to roll right into the hangar," he said.

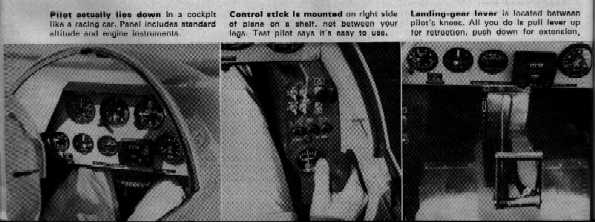

Having flown all my life with a center stick I wasn't really happy with the tiny control stick mounted on a shelf at the right side of the plane. You let your forearm rest on this shelf and move the stick mainly with your wrist. However, this is a matter of personal preference. Tests conducted by the U.S. Air Force on an F-104 jet fighter equipped with a "side stick" were highly successful. No dangerous malfunctions of any kind occurred. The pilots in the test were uniformly enthusiastic. They reported they could control the jet with less strain, and equal efficiency. Bede's little control stick is positioned in his plane at precisely the angle, and with the same angle of deflection throws, as the stick in the F-104.

The nosewheel is free-swiveling, he explains, so slowing is done with brakes. Touch the left brake; right, right brake. But aerodynamic control starts at 20 mph, when you can use the rudder. Directional control is not a problem. You can see the runway 10 feet in front of the nose, and once you're lined up and rolling for a takeoff there's very little need to use rudder. Just a touch, at intervals, to keep her straight then a little back-stick pressure with the wrist and she flies off by herself.

From the looks of things, the BD 5 may become one of the favorite acrobatic planes, along with the Decathlon, Zlinn, Pitts Special, and Chipmunk. There's already talk of forming a four-plane acrobatic team using BD-5's -- a sort of poor man' Blue Angels.

Berven has landed in many a stiff crosswind (Kansas is famous for them). He uses the standard "slip" method, and says he can handle winds up to 20 knots, which would put many other planes in the hangar, waiting for calmer weather. As a pilot with acrobatic experience who has flown an F-100 Super Sabre, I felt qualified to fly the BD-5. But no dice. "Put yourself in my place, Frank," said Jim Bede. "We have what appears to be a million-dollar baby here. I'm sure you're a capable pilot. I'm a capable pilot myself (Bede holds the world's record of 70 hours aloft without sleep) and I haven't flown it yet. This is our first real production airplane. Nobody -- not one single person -- has finished a BD-5 except us. Come back this summer. You can fly it all day."

I stopped arguing and accepted a cockpit checkout as the best onboard situation I was likely to get.

As for the Hirth engine, with its 6500 rpm at 75 percent power (the normal cruise setting), I was leery. I've been flying light planes for years and looking at 2500 rpm max on my tach. Bede said no sweat. You could run this Hirth engine all day at 6500 rpm and not hurt a thing. It has no valves, rocker arms, cams, springs, and the other moving parts found in standard, four-cylinder American lightplane engines. If they aren't there, as Bede said, how can they break?

The oil pump can't break, either, because there isn't any. You put the oil into the tank with the gas. It's a special synthetic oil that burns so clean, a carbon problem is rare. "One of the best things about the Hirth," said Bede, "is its low maintenance. All that's necessary in a top overhaul is to change the piston rings. The Hirth guy did it here at the plant in 71/2 minutes." Bede added that you can buy a new Hirth engine and install it in the plane for $500. It costs up to $500 for a major overhaul on a tired four-cylinder job.

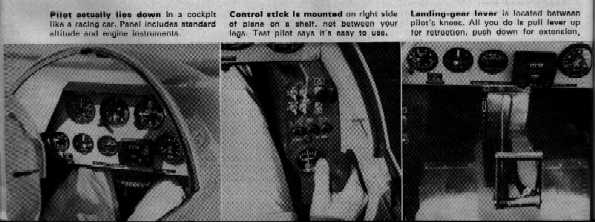

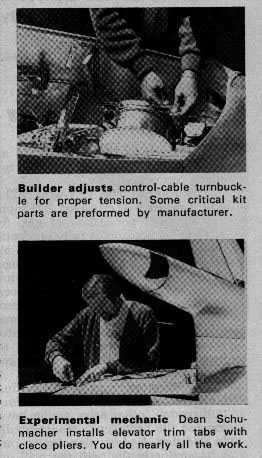

But wait a moment, there's a catch. You have to build the BD-5 yourself out of a zillion bits and pieces. Unless you're patient and like to cut, fit, and rivet, forget it. Bede freely admits you'll need at least six months, maybe a year, of nights and weekends to complete the job. However, he does make things as foolproof and easy as possible by sending you a thick I how-to-do-it manual that goes into every fine detail. (Editor's Note: The average construction time of a BD-5B is 3,000+ hours, quite a bit more than 6 months or a year of "nights and weekends.")

Most parts and drawings in the manual are full size. No need to scale down or rack your brain. Trace the shape off the manual and transfer it directly to the aluminum. Bede has not tried to cut costs by sending you large bulky sheets hoping you'll be able to get four or five parts out of each sheet without messing it up. He sends you one piece of aluminum per part. If you do goof up (and even an expert does at times) Bede has a warehouse full of replacements he will ship promptly at minimum charge.

Only "aircraft-quality" material is permitted in the BD-5. No saving nickels and dimes on little items that might screw up and put the entire airplane in difficulties. The main wingspar of the BD-5 (Jim’s trademark in all his planes) is a big thick aluminum tube that looks like a barrel. The wing ribs are close together for extra strength. Not only are the joints secured by rivets, but they are smeared with a special black gook called Proseal, which costs $23 a Pint, then pressed tight. The Proseal is like a weld. But it also has a rubbery consistency and soundproofs, weatherproofs, and makes every seal rock solid. There are, of course, some airplane sections that are so critical they can't be trusted to the skill of a homebuilder. These parts are preformed at the factory. They include ribs, spars, channels, fuselage bulkheads, and trim-tab panels.

This kind of thing is very dangerous. Even well-designed planes can be temperamental when rigged wrong, and someone skillful with tools may not be experienced as a pilot -- able to deal with a sudden emergency in his homebuilt.

Bede's plane, however, has been thoroughly flutter-tested, static-tested, stall-tested, and drop-tested. The parts are standard. Every key part is stronger than necessary, providing a comforting safety factor.

Bede provides a small light plastic "hangar trailer" to keep your little beauty out of the weather and to tow it to the nearest airport. The plane is available with optional electric starter, heater, and miniature instruments (if you can afford them) in addition to the standard panel: airspeed, altimeter, tach, compass, and engine gauges.

Bede has distributors all over the United States, in Canada, Switzerland, South Africa, England, Pakistan, Japan and Ethiopia. New Zealand is negotiating for rights to manufacture the plane and sell it ready-built in much of Southeast Asia. The reason for the plane's success isn't hard to see. Where else can you get a vehicle that carries you 200 mph for 11/2 cents per mile?

BD-5 Specifications

Maximum speed (sea level) 213 mph

Cruise Speed (7500 feet) 210 mph

Rate of Climb (sea level) 1480 ftm

Service ceiling 3,000 ft.

Fuel flow (75 percent power) 5.5 gph

Miles per gallon (75 percent power) 38

Optimum range (30 min. reserve) 1215 mi

Takeoff ground run 670 ft.

Takeoff ground run (over 50-foot obstacle)

830 ft.

Landing ground run 530 ft.

Landing ground run (over 50-foot obstacle)

830 ft.

Stall speed (full flaps) 55 mph

Stall speed (clean) 62 mph

Maneuvering speed 140 mph

Lift /drag ratio 21

(55–hp engine and long wing)

![]()

![]()

Web Author: Juan Jimenez

© 1999 by Juan Jiménez - All rights reserved.