It started with a classified ad in the local paper.

It climaxed with something approaching 10,000 people lining, in shifts, a dusty country airport runway to watch it fly.

The conclusion may be open to conjecture, but one thing is certain, Jim Bede's

BD-5 is the hottest subject in U.S. recreational aviation. It also may be a

hot subject in federal administration discussions, but those are privileged

and not yet open for public comment.It is clear that if he does nothing more,

or had done nothing previous to this, James Richard Bede, 40, has made a substantial

mark in aviation with his BD-5.

Doubtlessly, it has become the most controversial airplane of the decade. It

also is fast becoming the most popular airplane in the world; more than 4,000

people have signed up and begun paying their money for the privilege of building

it. And, obviously, thousands more are interested in it, as shown by the remarkable

turnout of people at the Bede Chautauqua sessions.

In a stroke of purely commercial genius, the Bede crew has taken the aircraft

to the people to demonstrate its reality. Many's the flight office design expert

who's said "she'll never fly," when confronted with BD-5 specs by a would-be enthusiast. The series

of public appearances is intended to allay just those comments and attitudes,

as well as demonstrate to the faithful that the BD-5 is, indeed, a viable airplane.

Thus the Bede BD-5 has appeared from Solberg Airport in New Jersey, to Livermore,

California, playing to thousands at the stops enroute. The finale of the show,

no doubt, was the appearance of five (count 'em, five) BD-5s at the annual

Oshkosh, Wisconsin, convention of the Experimental Aircraft Association. Even

the latest, jet-powered version of the "Five" was there, to hype interest to

the maximum.

If the shows were informal, the message was clear: "Here's the BD-5, just

like we promised; it's flyable, build-able, and available."

The classified ad we saw simply stated hourly flight demonstrations

from 9 a.m. til noon. The airport was Corona, in one of Southern California's

inland valleys, and the predicted temperatures were in the mid-90s. Also typical

was the morning haze that prevented flying until 10 a.m., and limited visibility

to about three miles all day.

Bede and the participating regional dealers set up shop in front of the field's

Piper dealership (with his permission, of course) and arranged displays and

counters for the dispensation of literature. The flying demonstrator

was parked conveniently in front, and off in the background was the world's

biggest portable BD-5 hangar.

Nothing formal, nothing really hucksterish about it; just a display and literature

if you wanted it. And, most importantly, people to answer questions about what

has been a most controversial subject, the BD-5.

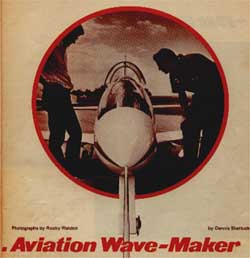

Then, flight time.The guy with the bullhorn asked people to move back, to

give the mini-missile room to start up and taxi in. Several handcranks later,

the engine came to life with a definite two-cycle staccato. Instantly, the

BD-5 began moving onto and down the taxi-way, as the horde of spectators cleared

a path for it. Everybody then rushed to the edge of the taxiway for the grand

entrance, the take-off.

A growing buzzing, a sound not unlike six bull hornets in heat, and the BD-5,

which is so small it looks like someone's toy airplane, came skipping lightly

down the runway. In less than 1,500 feet, it's nose came up, it lifted off

and the wheels were instantly sucked up into the wells. 'Whaddayaknow!

It really does; it really flies!

Looks of satisfaction, amazement, wonder, disbelief and relief washed quickly

over the throng. It was one of those times when you wished you had a movie

camera with a zoom lens, so you could capture the looks and replay them, time

and again. Though it didn't happen, you fully expected to hear a spontaneous

outburst of applause.

The little airplane quickly climbed upward into the murky skies, nearly disappearing from view. Nearly

as quickly, it had made a 180-degree turn and was snarling back down over the

field, parallel to but 50 yards north of the runway. It looked like a bullet

with wings. Zooming up into wingovers, test pilot Les Berven did lazy eights

for several minutes, with the bottoms of the eights 100 feet off the ground

near the runway. Then he gave the Gear Retraction Demonstration: flying at

medium speed parallel to the runway, at low altitude, he repeatedly cycled

the gear, showing

that it extends and retracts in near split-seconds. Then, a couple of more

zooms and it was into the pattern for landing.

Surprisingly enough, it came around at moderate speed, lowered softly to the runway, and rolled to a halt with no fuss, muss, or fluster. Ground handling problems? Zero. At least not on Corona's paved surfaces.

As flight demonstrations go, it wasn't terribly inspiring.

As a demonstration that the BD-5 was what Jim Bede claimed it would be two

years ago, well, it was a roaring success. It obviously took off,

climbed, cruised, and landed without glitches, without mishap. Admittedly,

the performance was professional; Berven, as far as we've been able to determine,

is the only person (perhaps other than Jim Bede himself) to have flown a BD-5.

The performance was repeated at hourly intervals as advertised until early

afternoon. Then, when most of the people had departed, the wings came off the

Five and it was stuffed back into its transporter, a shiny big DC-3 with cargo

doors, for a trip to Livermore, California, and the show

scheduled for the next day. The DC-3 carries the "BD" logotype and red striping

just like the decoration on all other Bede aircraft. The traveling performances

must have been terribly satisfying to both Bede and his believers. They'd said

all along that it would fly, that the home-builder could put it together and

fly it. There were plenty of people who said it would never happen; plenty

of detractors, including a lot of well-qualified skeptics. But, there is was,

for all to see.

A closer examination of the BD-5, plus the realization that it has taken two

years of hard work by a lot of dedicated people to get it to this point, brings

the realization that dreams just don't come true by wishing them that way.

It takes skill, money, dedication, and a lot of intestinal fortitude on Bede's

part. The BD-5 "Micro" has developed enormously in the last two and a half

years, and if it doesn't quite meet those original, optimistic expectations,

it isn't because the Bede Aircraft design/development team isn't trying.

The original wild sketches of the Micro showed a vee-tailed, long-snouted

little creature that fairly well resembles what's in the air today, though

the vee tail long since has disappeared and the snout has been bobbed slightly.

Though a bit more rounded and fuller than the first concept, the Micro nonetheless

is better, more realistic looking.

Those first, optimistic releases quoted 205 mph on 32 hp,

and a kit cost of $1 ,800. The fuselage was to be an aluminum truss with a

fiberglass shell. The belt drive to the extended pusher prop shaft was to be

a variable one, to let the engine develop maximum power for take-off and climb.

Range was quoted as 600 miles . . .65 miles per gallon and a 10-gallon fuel

tank. There were to be split flaps, and ailerons carved out of solid balsa

wood, for easy construction. The wing was to be aluminum bonded to ribs over

a tubular spar. Empty weight was projected at 210 pounds, of which the manually

retractable landing gear was to weigh only 10 pounds. Preliminary calculations for the

70-hp version were even more optimistic: over 265-mph

cruise, etc., and stall speed below 60.

First to go was the vee tail; a conventional vertical fin and stabilator design was quickly adopted, to give the Micro more stability. The split flaps and balsa ailerons disappeared nearly as fast, giving way to more conventional design in simple trailing edge flaps and built up aluminum ailerons. Wing skin was flush-riveted instead of bonded, and the fiberglass fuselage, which warped out of shape from engine heat on the prototype, gave way to conventional aluminum monocoque, built up from formers and preformed skins, with more flush riveting.

Only the longer, 21 1/2 foot wingspan versions have been flown, though the

shorter, 14.3-foot wings have been built. The earlier speed and performance

projections were based on the shorter wings.

With the full 70 hp and the short wings, original speed projections still seem

optimistic: the long-winged, mid-powered current production prototype logs

over 185 mph, though not quite developing maximum power. There

were no speeds announced during the prototype demonstration, and it is

nearly impossible to estimate them because of the Micro's deceptively

small size.

Stall speeds, on the other hand, now are down to the low 60s, for the long-wing

prototypes, which is no better nor worse than many other homebuilts. Obviously,

the short-wingers are going to be somewhat hotter on approach and landing.

The landing gear, too, has made a full metamorphosis, with wheel size increases,

longer struts on the main gear, and completely redesigned oleo nose-gear. The

manual gear retraction system and related doors also have been redone, and

the newest set-up is said to work like a charm. Indeed, the fly-by cycling

showed that it popped up and down faster than a fiddler's elbow.

While the engine department has been another element of development, the drive-train system has not. Though the original plan called for variable-speed drive (because the prop shaft is driven by rubber vee belts and pulleys, it's possible to vary the pulley diameter and thus change its drive ratio), so far only the fixed ratio system has been used. At 1.6:1 drive ratio, the propeller is turning 3,750 rpm though the engine is running at 6,000 rpm. The rubber vee-belts also have an another important function, that of cushioning power impulse shock loads between engine and prop shaft.

The engine problem, that is, which one to use, and how much power it would

develop, etc., was still in the air (figuratively and literally) little more

than a year ago. Jim Bede was convinced that one of the current crop of snowmobile

engines (high horsepower output with relatively low weight, air cooled two-cycles)

offered the best possibilities. In the end, he has settled on the German-made

Mirth engine, which is available in three displacement (and power output) sizes. One

advantage of the Hirths: they already were being used in several

European-built motorgliders, thus the peculiarities of adaptation to aerial

use already were understood by the factory engineers.

The Hirth is a two-cylinder, two-cycle, which means it fires twice every revolution,

just like a conventional four-cylinder four-cycle engine such as a Lycoming or

Continental. (A two-cylinder, four-cycle engine such as the Franklin fires

only once per revolution.) But, because the cylinders are in line, rather than

opposed, the power pulses of the Mirth develop what engineers call a rocking

couple, which translates itself into a heavy throb or vibration. Motor- cyclists

well know what we're talking about. The vee-belt drive damps this pulsing, thus protecting the long

propeller driveshaft and supporting bearings.

Though the choice of a two-cycle engine is a bit unusual for an aircraft, there

are definite advantages in weight and simplicity-advantages that have made

two-strokers the champions of motorcycle (and snowmobile) racing where very

light weight and high power output are equally important factors.

The biggest Hirth has 720 cubic centimeters (43.5 cubic inches) displacement,

which is roughly half that of a Volkswagen, and is said to produce 70 horsepower in aeronautical form.

Weight is 72 pounds. The four-cycle VW, on the other hand, produces slightly less

than that and weighs approximately twice the Mirth, even when stripped for

airplane use. The

Mirth probably burns as much fuel as the VW, plus it has the full loss oiling

system that must be used with two-strokers.

Through Bede's efforts (the sale of 4,000 and more engines must be a powerful influence at the Mirth

factory), Mirth engineers have developed dual ignition for two of the three

engines available, and have made carburetion more suitable to aircraft use.

The latest carburetor doesn't need mixture adjustment below 7,500 feet

altitude, according to test pilot Berven.

The 40-hp version is the standard engine, but Bede sales people are recommending

the optional 55- or 70-hp models for better performance.

| HP | Disp (cc) | Weight (lbs) | Ignition |

| 40 | 440 | 68 | Single |

| 55 | 650 | 73 | Dual optional |

| 70 | 720 | 72 | Dual optional |

Bede Information Memo No.14 has this to say about engine selection: "The best

overall engine for the BD-5 is the 720 cc (70 hp) engine. It not only provides

the aircraft with the greatest amount of power, which results in shorter take-offs

and better rate of climb, but it gives the pilot the option of very high cruising

speeds or the capability of throttling back to lower power for lower fuel consumption.

This engine is also the most desirable because it features the new cylinder

design specifically for aircraft operation. The power-to-weight ratio is by

far the best of the three engines.

"The next choice is the 650 cc (55 hp) which also is available with dual ignition

but has no other real advantages, except that it is available at lower cost".

"The 440 cc (40 hp) engine is a minimum consideration. First, dual ignition is not available and, second, although our aircraft has been performing satisfactorily on 40 hp, take-off distances have not been longer than we desired . . . rate of climb with gear down was not the best. Although this engine is the least expensive, we believe the savings are not justified considering the total time and money spent on the project."

As things have become finalized, and more and more of the construction kit

packages have been shipped out, the Bede development crew headed by Bert Rutan

have cast their eyes increasingly afield. One of the more attractive sights

they've seen is the miniature Italian turbothrust engines used in the Caproni

A-21J jet sailplane. The Sermel TRS-18 weighs only 66 pounds and develops 220 pounds maximum continuous

thrust-more than enough to push a BD-5 at highly impressive rates of speed.

In typical Jim Bede fashion, some pretty wild claims for performance are being

handed out for the BD-SJ. Try cruise speed of 325 mph at 25,000 feet; rate

of climb (sea level) of 3,000 feet per minute; maximum speed 350 mph! Kit price,

in the $20,000 range.

Impossible? Improbable? Better not say that. Better just say, "wait and see." Jim Bede has a track record of making dreams come true, even if it always seems to take a little longer than he originally estimates. His credo might well be the same one we've seen stuck up on engineering shop walls: "The difficult job we'll finish tomorrow, the impossible one just takes a little longer!"